A veteran of marine mammal conservation has a new book with a startling message: To save an entire species, we need more hands on deck.

Dr. Michael Moore, a senior scientist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, got his first up close look at the lives of whales in the summer of 1979. They were humpbacks, feeding on capelin near the fishing village of Bay de Verde, Newfoundland. Moore was watching them from his official research vessel — a leaky, 28-foot wooden sailboat.

“At the time, it was pretty informal, and you did what you did,” Moore said. He was aboard at the behest of Hal Whitehead, a biologist whose groundbreaking studies of culture and social behavior among whales revolutionized understanding of these complex animals.

Soaking in Newfoundland and Labrador’s cornucopia of marine life, sailing through ice and fog, and exploring abandoned whaling stations, Moore became entranced by cetaceans.

Since then, the study of marine mammals has matured, and Moore has matured with it. He joined WHOI in 1986, and has been involved in nearly every facet of cetacean conservation on the East Coast — as a biologist, as a veterinarian, and, all too often, as a mortician.

Moore’s decades in the field were accompanied by a growing sense of urgency about one species in particular, the North Atlantic right whale. His new book, We Are All Whalers, looks back at his own life and forward to the tenuous future of these imperiled behemoths.

He spent his career learning how to save right whales on an individual basis, with some success. “But,” he writes, “I also knew that prophylaxis had to be the ultimate goal of any veterinarian.” To save an entire species, Moore warns, we need a lot more hands on deck.

Studying the Outliers

The path that led Moore to whales began at Cambridge University, where he became interested in marine mammals because they were so often anatomical and physiological outliers in the animal kingdom, the exceptions that his professors used to demonstrate a rule.

Chasing this curiosity, he finessed his way to the Faroe Islands to study the whale hunt. He also made contact with Hal Whitehead, who was doing a PhD on humpback biology and Whitehead invited Moore to sail with his research crew in Canada and eventually the Caribbean.

Moore’s book is full of these providential connections. “My wife describes the book as a sort of justification for being a peripatetic,” Moore said, smiling. “Taking what opportunities come your way.”

A journal entry from January 1980 finds Moore anchored in a 33-foot sloop on Silver Bank, north of the Dominican Republic, on the wintering grounds where humpbacks calve and mate. “Now anchored in the deep part of the bank,” he wrote, “not much wind and lots of singers, very beautiful, very tired. Songs can be heard through the hull. This is a very special place.”

Against this idyll, Moore juxtaposes his experience aboard an industrial whaling ship in Iceland in 1983, where he saw the effect of explosive harpoons on fin whales. The experience “became the sort of end stop,” he said. “Okay, if you're going to go kill whales, this is how to do it efficiently.”

“Most whale biology prior to 1980 was gleaned from whaling trips,” Moore said. Historian D. Graham Burnett described these scientists as “hip-booted cetologists” for their wade-and-see approach. Their utilitarian outlook was challenged by new work in ecology, genetics, and especially acoustics that began to paint an astounding picture of life as a whale.

Among the early trailblazers of this new field was another WHOI scientist, Bill Schevill, who with his wife, the zoologist Barbara Lawrence, recorded the first underwater whale songs in 1949 — a phonograph of Beluga whales calling to each other.

When Moore came along in the late 1970s, he met Roger and Katy Payne, whose bestselling bio-acoustic album “Songs of the Humpback Whale” helped catalyze the worldwide “Save the Whales” movement and the global moratorium on whaling in 1972.

Although he is a scientist, Moore feels he also must advocate for whales, “by the nature of a veterinarian's commitment to the health of their patients,” he said. “Certainly, I’ve become more of an advocate than I was, say, 20 years ago. I feel like I have a basis of knowledge and perspective that has some value in terms of where to advocate and how to do so.”

The Cape, the Islands, and the Right Whale

Moore’s specialty is right whales, and despite the increasing efficiency of rescue operations, they are dying at an alarming rate. By 2021 their populations had declined for 10 straight years, according to the New England Aquarium, and are now down to roughly 336 individuals. There are fewer than 100 breeding females.

Like many on the Cape and Islands, Moore watches whales from the deck of a boat, often in the early spring when they congregate here with their calves. With the typical ingenuity of oceanography in Woods Hole, he’s also figured out how to give a whale an ultrasound in the wild, and he helped invent a whale-sized dart gun to sedate whales during rescues at sea.

He also became a sort of coroner for right whales wherever they died — whether it be Maine or Florida. “Basically, I had to be ready to grab a box of tools and be on a flight that same day,” he said. “Quite often I'd be waiting on the beach when they towed it in the next morning.”

His work left little room for doubt about the cause of the whales’ decline. “Veterinarians are trained to look at live and dead animals, to take them apart when they're dead, figure out how they died and why, and do something about it,” he said.

Necropsies overwhelmingly implicate shipping traffic and trap fishing. Some whales are injured and killed in collisions with large vessels traveling at speed. Others are entangled in lobster or crab traps as they swim, mouths agape, through swarms of their favorite food.

“North Atlantic right whales tend not to die of old age,” Moore writes. A recent study found that entanglement in fishing gear or strikes from vessels were responsible for 88% of all known causes of death for right whales between 2003 and 2018.

The North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium keeps a catalog of all right whales ever photographed. By identifying unique features on each whale, this system allows them to track individual whales over time, so the whales that Moore studies often have years of observational data to draw from.

When scientists reviewed the catalog of known whales, they found that 83% of the animals carried scars from entanglement in fishing gear, 59% had been entangled more than once, and 26% received new scars every year.

A journal entry from January 1980 finds Moore anchored in a 33-foot sloop on Silver Bank, north of the Dominican Republic, on the wintering grounds where humpbacks calve and mate. “Now anchored in the deep part of the bank,” he wrote, “not much wind and lots of singers, very beautiful, very tired. Songs can be heard through the hull. This is a very special place.”

In other words, nearly all right whales find themselves caught in rope at some point in their lives. The outcome, if not deadly, is an agonizing drag on their health and reproductive capacity. In the past, right whale mothers were able to produce a calf every three years, but changing food availability and trauma have extended this interval in some cases up to twelve years.

“Very often they don't die, but they will nonetheless suffer energy loss from towing the gear around until they are disentangled or they lose it themselves,” Moore said. “In so doing, the chance of being a successful reproductive unit decreases, because their energy is being drained. So two things happen: one is that reproductive success decreases, and also mortality increases.”

Since 2017, so many right whales have died that NOAA has declared an “Unusual Mortality Event.” Moore is no longer wading into whale carcasses. “I got a kidney transplant in 2016, so I've been less directly involved in dead, stinky stuff,” he said. As he stepped back from necropsies, he began to focus more on the existential threats to the species as a whole — and what we can do about them.

We Are All Whaling

The relics of old whaling dot the Vineyard — the church in Edgartown, the antique scrimshaw on Islanders’ shelves, and the logbooks of whale ships at the Martha’s Vineyard Museum. Whaling is part of the Island’s foundational story, but few would think of it as a whaling port today.

In Moore’s view, though, we are all still basically whaling. “Few humans eat whale meat anymore, but fishing techniques unintentionally harm and kill whales,” Moore writes. “Even vegetarians contribute to the problem, as we all benefit from global shipping of consumer goods and fuel, which, in its current iteration, leads to fatal collisions with whales.”

The relics of old whaling dot the Vineyard — the church in Edgartown, the antique scrimshaw on Islanders’ shelves, and the logbooks of whale ships at the Martha’s Vineyard Museum. Whaling is part of the Island’s foundational story.

In recent years, dead whales have been found off the Vineyard, Nantucket, and the Elizabeth Islands, several of whom likely died from entanglement. They are a fraction of the 50 that have been killed or seriously injured just since 2017, according to NOAA.

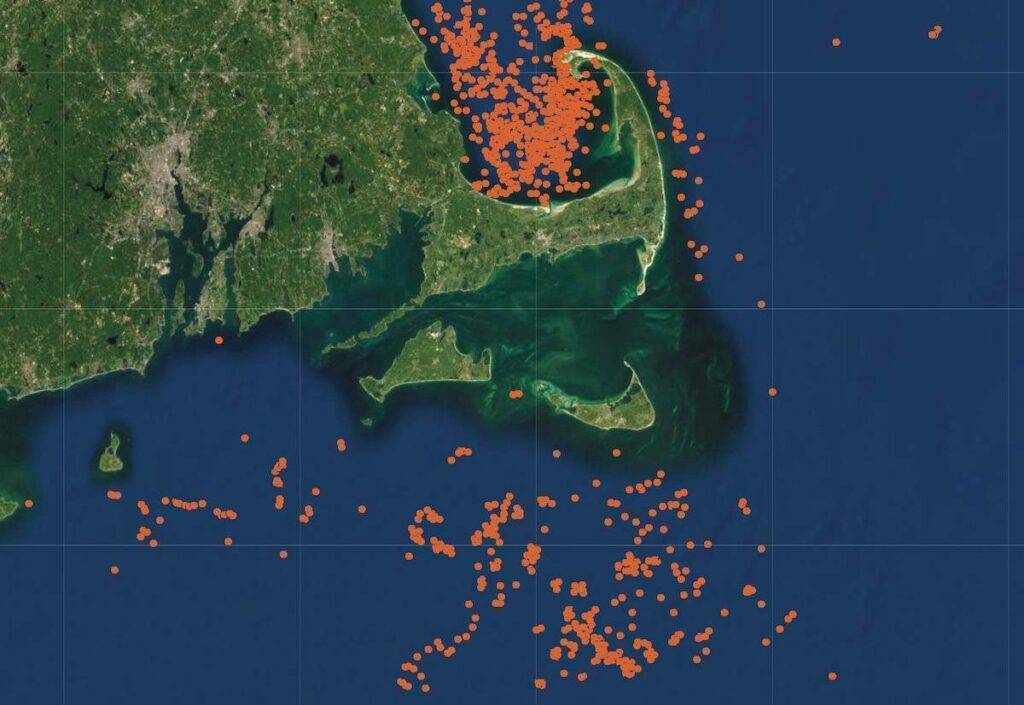

Since right whales range anywhere from Newfoundland to Florida over the course of a year, there’s often no telling where they become entangled, but recent estimates put the number of vertical end lines in Northeast waters at nearly a million, and the overwhelming majority of these lines are attached to lobster gear.

“The very presence of that rope creates a very significant entanglement risk for right whales, humpback whales, and leatherback turtles,” Moore said. “So, every time we as individuals purchase a lobster, whether we home cook it or eat in a restaurant, we are incrementally enabling an industry that poses a significant entanglement risk.”

Although climate change means that many more whales are spending their time in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, rather than the Gulf of Maine, the U.S. is still host to the whales’ breeding sites. “So they're moving through coastal waters in the U.S., and will be, I suspect, for as long as the species is around,” Moore said. As feeding patterns and water conditions have changed, Cape Cod Bay has become more important to whales, as have the waters south of Martha’s Vineyard.

“Conservation of endangered large whales is an endless cycle of recognizing a problem, documenting it, designing and implementing solutions, and monitoring their effectiveness,” Moore writes. Then, when conditions change, “another turn of the cycle must begin.”

Reducing vessel strikes has proven to be more tractable than fishing without rope. Re-routing shipping lanes or setting speed limits in areas of high whale activity has been effective in some cases, especially when implemented in tandem with real time observations. But Moore warns that climate change is making the locations of whales harder to predict, and much more will need to be done to safeguard them from vessel strikes.

As for getting rope out of the water column, the problem is more existential. “Wherever rope and whales coexist, there is entanglement risk,” Moore writes. The only viable solution, and the one he’s been working to develop, is to replace vertical ropes and buoys in the water column with remotely deployed gear that can rise to the surface when triggered by a fishing boat.

Of course, many see this as not, in fact, viable — especially lobstermen. The technology is costly and still being developed, and if these new techniques are to be widely adopted, they will have to overcome intransigence of fishermen. Moore knows a few who are willing to give it a try, and hopes their success will convince a few more.

“Regulations are coming into effect to enable people fishing ‘on demand’ in areas otherwise closed for marine mammal conservation,” Moore said. “Right now there are regulatory opportunities to do that both offshore in the Gulf of Maine and in Eastern Massachusetts.

The devil is in the details, and the folks that want to do that need to get experimental fishery permits, which take a while to get.”

Moore warns that climate change is making whales’ locations harder to predict, and much more will need to be done to safeguard them in the United States.

The people trying to solve this problem are themselves entangled in a binding of a legal sort — caught between laws old and new, which conflict with each other and make change difficult. For example, any attempt to use remote activated trap gear has to contend with longstanding laws that require traps to be marked by a surface buoy.

“And climate change is driving offshore wind, and what's that development going to do with the fisheries and whale sustainability?” Moore asked. “We don't really know yet. It's complicated. And it'll be hard to pin the tail on the donkey as well. So, it's a glorious mess.”

In 1994, when the U.S. government amended the Marine Mammal Protection Act to limit the mortality caused by fisheries, Congress required that animal deaths not exceed a limit that would threaten a species’ survival. “For North Atlantic right whales,” Moore writes, “this limit has remained close to zero. In other words, if the species is to persist, no more whales can die.” This goal has never been met.

“The fate of these animals is in the hands of you and me in terms of our consumer decisions and our political pressures,” Moore said. “If we carry on with the status quo, I think we're in deep trouble. Think about where we're headed. We're going to be standing in season on the beach, looking out at a naked ocean. And that ain't good. So, what do we care about? That's the question.”

What You Can Do

- Push legislators and industry to adopt ropeless gear for lobster harvesting

- Consider cutting back on lobster dinners (try Monkfish — which has a similar taste)

- Check out whale sightings at whalemap.org

- Learn more by visiting recent log entries from the Martha’s Vineyard real-time whale detection buoy

- Listen to Northern Right Whale acoustic recordings from WHOI’s Watkins Marine Mammal Sound Database